We’re wired to feel. Not just the good feelings but the messy, sweaty, crazy, fierce ones too. Feelings drive our aliveness, our relationships, our decisions and our humanity. It’s how we connect, love, decide who’s right, who’s not, what’s good for us and what we should steer clear of. Most importantly, feelings are the clue that something isn’t right and needs to be dealt with. They direct us to what we need to find balance.

Sadness is a cue to reach out to our tribe for emotional support, happiness tells us to keep doing what we’re doing because it’s doing us good, fear is a warning and readies us for fight, flight or freeze. And then there’s anger. If it’s not managed well, anger will break hearts, relationships, lives and people. If managed well, anger can be protective and motivating. Plenty of good things have happened throughout history because people got angry enough to make a difference.

All feelings are important and have a place in our lives. If they didn’t, thousands of years of evolution would have got rid of the useless ones by now. We can pretend that uncomfortable feelings don’t exist, but that won’t make them go away. Denial buries feelings somewhere deep inside us and when little seeds are buried, they grow.

The more children are able recognise what they’re feeling, the more they can experiment with an effective response and the less control those feelings will have over them. It’s never feelings that cause trouble, it’s what we do with them. Here’s how to explain anger to kids and teens …

Explaining Anger to Kids & Teens.

Tell them why it’s important.

Every feeling we feel has a really good reason for being there, even anger. It might not always spring to life at the best moment, but its reason for being there will always be a good one. The problem is never the feeling, but how that feeling dealt with. Feelings cause trouble when they sneak up from behind and grab on, bear hug style. When that happens, it can feel like that feeling has complete control, which it kind of does for a while. The key to being emotionally savvy and not being barrelled along by intense, powerful feelings is to turn and face them, feel them, and bring them back under control.

Anger has a number of good reasons for showing up.

-

It lets people know what you’re feeling (without you saying a word!)

Emotions change the way we hold our body, the expression on our face, our response to situations or to people, the type of thoughts we think and the memories that come to us. You can usually tell when someone is angry just by looking – and people can tell the same thing when the angry one is you. The way your face looks when you’re angry, and the way your body expands to looks taller and stronger can be a warning to others not to come too close. It can also let people know they’ve upset you.

-

It’s energising.

Anger feels bad, but what would feel even worse is being in a bad situation and not realising it, or realising it and not having the energy or motivation to change it. Anger helps us to know when something isn’t right. When something happens to make us angry, the brain releases chemicals (oxygen, adrenalin, hormones (particularly cortisol – the stress hormone) to fuel our body and give us the energy to something about the problem.

-

It stops intense, difficult feelings taking over.

Anger is the only emotion that never exists on its own. There is always another, more powerful emotion underlying it. When an emotion feels too intense, or when the environment feels unlikely to support that emotion, anger is a way to stop that difficult feeling taking over. Some common underlying emotions are fear, grief, insecurity, jealousy, shame. When these feelings feel too intense, anger can be a way to hold them down until the intensity of them dies down a little, or until the environment feels safer and more able to respond and help us feel better. Anger can be pretty handy like that, provided it doesn’t become a habitual response. All emotions are valid, and it’s important not to shut any down for too long. Being able to recognise, acknowledge and feel the full spectrum of emotions is an important part of healthy living.

Explain why anger feels the way it does.

Here’s how to explain it to the younger ones in your life …

Anger is an emotional and physical response. When something happens to make you angry, your brain thinks it has to protect you from danger so it releases chemicals – oxygen, hormones and adrenaline – to fuel your body so it can fight the threat or run from it. Here’s what that feels like:

• Your breathing changes from slow deep breaths to fast little breaths. This is because your brain has told your body to stop using up so much oxygen on strong breaths and to send it to your muscles so they can protect you by running or fighting (even though we all know that fighting is a bad idea!)

• Your heart speeds up to get the oxygen around your body so it can be strong, fast and powerful.

• Your muscles feel tight. This is because your brain has sent fuel (hormones, oxygen and adrenaline) to your arms (in case they need to fight the danger – but you probably won’t want to do that) and to your legs in case they need to run from it (okay – you might want to do that.)

• You might feel shaky or sick in your tummy. This is because your digestive system – the part of the body that gets the nutrients from the food you eat – shuts down so that the fuel it was using to digest your food can be used by your arms and legs in case you have to fight or flee.

• You might feel like crying. Crying helps to relieve stress – it’s the body’s way of calming itself down.

• You might feel like yelling (to fight the ‘danger’) or running away (to escape it).

• You might feel like hurting someone. This is really normal, but remember that if you hurt someone with your words or your body, it will always land you in trouble. An angry brain is great at fuelling you up to be strong, fast and powerful, but not so great at thinking things through. Don’t believe it when it tells you to fight or hurt people or things. Here’s why …

What happens in your brain when you get angry?

Brains have been practicing anger for millions of years, so they’re pretty excellent at getting you ready to protect yourself from whatever it is that’s made you angry. When something happens to make you angry, your brain fuels you up quickly and automatically to respond. The problem is that an angry brain isn’t always the smartest brain and just because it’s telling you to respond a certain way, doesn’t mean it’s the best idea.

Your brain tries to make you strong, fast and powerful – kind of like a superhero – but anger can make people make really dumb decisions. When you’re angry, your intelligence drops by about 30%, so you’ve got awesome speed and strength, but your brain won’t be thinking so clearly. That’s a dangerous combo and if you don’t get a hold of your brain and set it on the right track again, you could end up more of a villain than a superhero. There’s nothing wrong with feeling angry. Everyone gets angry from time to time. The difference is that heroes are thinkers and they don’t hurt people. The not-so-heroic make silly decisions and even if they don’t mean to, they hurt people along the way.

There’s a simple difference between the two and it’s about which part of the brain is in charge. Here’s how to make sure you’ve got the right part working for you.

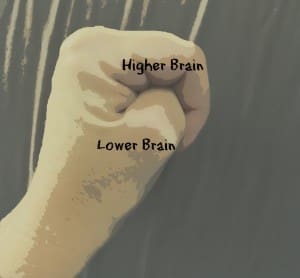

Try this … Make a fist so your fingers are curled over your thumb. Now, as explained by neuropsychiatrist Dr Dan Siegel, imagine that this fist is your brain. At the top are the higher parts of the brain that help you think clearly. (In your real brain, it’s just behind your forehead). This part of the brain is responsible for reasoning, using all the information you have to make good decisions, your creativity, and your intuition (listening to your heart and that little voice inside you that tends to know what’s best for you).

Then there’s the lower part of your brain. This part helps to control the physical processes that keep you alive – breathing, blood pressure, seeing, hearing, tasting, listening, sleeping. It’s also responsible for instinctive behaviour, which is when you respond to things automatically, super-quickly and without really thinking. Instinctive responses keep you safe. If there’s, say, a lion coming at you, you could be in a bit of trouble if you had to take time to think about whether or not you should get out of the way.

The bottom part of the brain responds to things without a lot of thought. It’s automatic, instinctive and impulsive. It’s great when there’s real danger, but not so great when situations need more thought and consideration – which is most of the time. This is why you need the higher brain to be in charge. When it’s involved in behaviour, you can be reasonable, flexible and thoughtful. You’ll still do everything you need to do to keep yourself alive, but you’ll do them sensibly and when you actually need to.

When you get angry, the lower brain takes over. It gets so activated that it floods the higher brain and stops it from working. Without your thinking, sensible higher brain, your lower brain can get up to some crazy stuff.

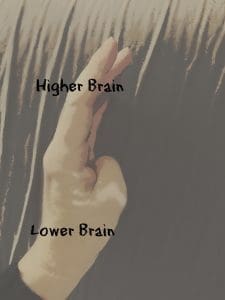

Remember that the lower brain does things without thinking, so it can get a bit reckless when the higher brain isn’t in control of it. The part that co-ordinates your higher brain and your lower brain exists behind your forehead. When you get angry, that area stops working and the higher brain disconnects from the lower brain.

Remember your closed fist? Start to open it (but keep your thumb where it is). See how the top part of your brain (pretend it’s your fingers) is kind of disconnected from the bottom part? This is what happens when you get angry. Of course, your real brain doesn’t come apart but what does happen is that the higher brain no longer has control of your lower brain, which becomes free to do whatever it wants. This is when things can get a bit ugly. You might yell, scream and feel like you want to break people or things. Until you bring your higher brain back to the control deck, the lower brain will be doing all sorts of things that could land you in trouble. You feel out of control, it’s because you kind of are – out of the control of your thinking, sensible higher brain, to be exact.

There are plenty of ways to reconnect your higher brain to your lower brain, and bring your anger under the control of a brain that is sensible, smart, creative, and able to come up with great ways to respond to things.

What to do when you’re angry.

Anger can be a great thing when it motivates you to make a difference in ways that don’t hurt anyone. The truth is that when you hurt someone else, it will always end up hurting you eventually. You don’t want to be that person who just goes around letting the angry, impulsive, reckless part of your brain making you do dumb things – you really don’t want that. Anger can be a great thing. It can be the reason you protect your friend or the new kid when the bullies are giving him a hard time. It can be the reason you put wrong things right – but only if you have control of your brain while you do it. Otherwise it’s a mess. A dreadful mess. You could hurt someone’s body, feelings, things, and you can do or say things that can’t ever be put right.

Be the boss of your brain and you’ll be the boss of your anger. You can use it to do awesome things – to motivate you, inspire you and to make wrong things right, but seriously, you’ve gotta be the boss of your brain for that to happen.

[irp posts=”1247″ name=”Kind Kids are Cool Kids. Making sure your child isn’t the bully.”]

You don’t necessarily want to get rid of your anger – it might be trying to tell you something important. What you want to do is control it. You need to reconnect the thinking, flexible, higher part of your brain back to the impulsive, unthinking lower brain. When that happens, you’ll be back in control, you won’t be hurting anyone (you might still feel like you want to but you’ll know how dumb that would be and you’ll be able to stop yourself), you won’t be yelling and you’ll be able to make clear decisions and find great solutions. Here’s how to do that:

-

Breathe. Sounds simple – and it is – but there’s a reason for that.

There’s a reason we practice breathing every single moment of every single day. The first is that if we don’t we die. The second is that when you breathe your brain releases chemicals that calm down the angry feelings. Anger goes down. Smarts go up.

-

Take a walk.

Walk away and go somewhere else until you brain is back under control. You want to be as smart as you can if you’re having to deal with someone who has ticked you off, and the only way you can do this is to get your brain sorted. It will happen on its own, and it doen’t take long, but sometimes you have to find some space so that can happen.

-

If you want to be heard, be calm.

Say what you need to say in a calm, clear voice. When you yell people won’t hear your message. All they’ll hear is that you’ve lost your mind, which, if you’re angry, you kind of have. Get it back and you’ll say things that make a lot more sense because you’ll have your full brain with all of your smarts, not 30% less.

-

Get active.

Go for a fast walk, a run, a ride, or turn your music up and dance really hard – anything that gets you moving. Getting active will help your body to get rid of the ‘angry’ chemicals that your brain has fuelled you with to help you fight or run away. If you don’t fight or run away, these chemicals can build up and make you feel even worse. It’s easy to mistake them for feeling angrier and angrier, when actually what your feeling is your brain saying, ‘come on – I’ve given you want you need to be fast and strong – use it!’ Being active will burn the chemicals and help to settle your brain again.

-

Decide on the type of person you’re going to be.

Using your body or voice to hurt others is never cool. Decide that you’re always going to be better than someone who loses it. If you have to, talk to an adult who can help you. For sure they would have felt angry before and can talk you through yours. Adults can be pretty great like that.

-

Give permission to all of your feelings to be there.

Anger is the feeling we grab on to, to keep more difficult, intense feelings under control. Anger never exists on its own and it can be really helpful to understand what feeling is beneath it. Breathe into yourself and be open to any other feelings that might be there. Just let it happen. They’ll show themselves to you when you’re calm, still and open to seeing them. When you can find the feeling beneath your anger, your anger will start to ease.

-

Get to know your triggers. (We all have them!)

Know the things that tend to make you steam. Are you someone who gets angry more easily when you’re tired? Stressed? Hungry? Once you start to recognise your triggers, you can work towards making sure you limit those triggers when you can.

Anger is a really normal thing to feel. As with anything, it can be a great thing or a not so great thing. To make it something that’s helpful, it’s important to make sure that your higher brain doesn’t disconnect and leave your lower brain in control of things. Your lower brain loves doing what it wants, and will get you into all sorts of trouble if it’s left in charge. Learning to bring your higher brain back is something that takes practice, but the person who is the boss of his or her brain will always be someone pretty awesome.

This is so helpful in understanding my 13 year old’s unexpected anger (usually around homework time). Thank you!